- HOME

- Ionian Islands

- Corfu

- Visiting Albania From Corfu

Visiting Albania from Corfu

Donna Dailey visits Albania by boat from Corfu Town, staying overnight and seeing archaeological sites with Sipa Tours.

The Germans have a joke: ‘Go to Albania on holiday. Your Mercedes is already there.’

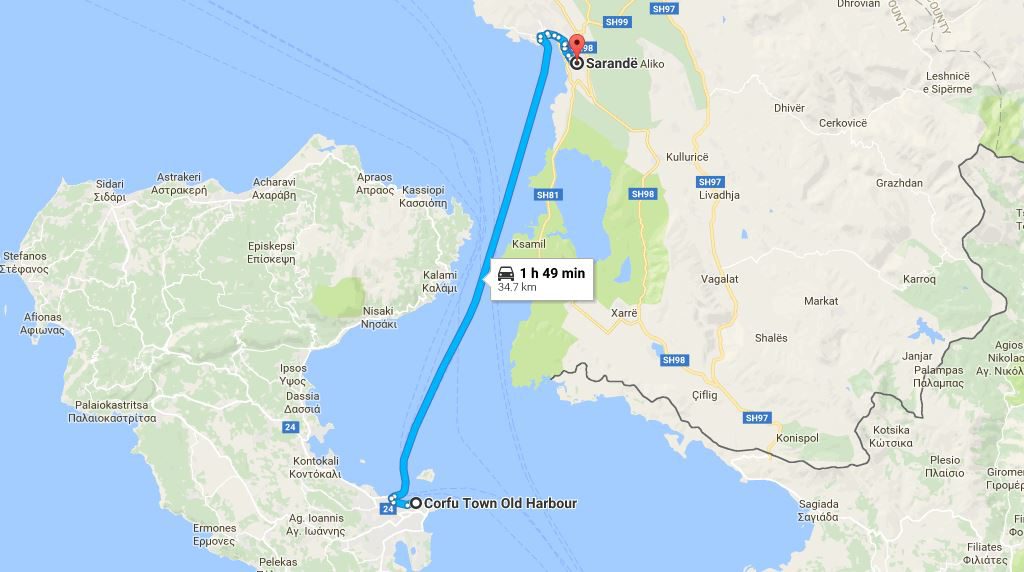

It’s a sardonic comment on the thriving black market in stolen cars, allegedly run by the so-called Albania mafia. And judging by the number of Mercedes we saw when we got off the ferry in Sarandë, many people may not find it too funny. The streets are literally lined with them. The profusion of this status symbol in one of Europe’s poorest countries is just one of Albania’s many anomalies.

After the Second World War, the Stalinist dictator Enver Hoxha came to power, eventually sealing Albania’s borders and cutting it off from the outside world. For decades it was the most isolated and backward country in Europe. The border only reopened in 1991, six years after Hoxha’s death. Now under democratic rule, the country has struggled to shake off the financial and social legacy of its communist years.

While the capital, Tirana, is the focus of business and government, the southern tip, bordered by the Greek mainland and the Adriatic and the Ionian seas, is the most ripe for tourism. The island of Corfu is only 2km (1.2 miles) away at its nearest point, and a ferry from there is an easy way to visit. we made my first trip to Albania in 1995, but the growth of its then-fledgling tourism effort was halted two years later when angry mobs took to the streets following the collapse of a fraudulent pyramid investment scheme.

Now I’m returning with Arben (Ben) Cipa, a young Albanian who runs Sipa Tours with his business partner Ingrid, a Dutch national who lives on Corfu. On the island, Ben is known as Sotiros. As a teenager he left Albania seeking better opportunities, and even took a Greek name.

Arriving at the port, we find the old Stalinesque concrete apartments are now flanked by shiny new hotels. Old women in black dress and headscarves eye the passengers as they spread out piles of vegetables to sell on the pavement. Nearby the money-changers line up with thick wads of notes in their hands.

We’re directed to show our passports at a new building. ‘This terminal wasn’t here 10 years ago,’ we remark.

‘It wasn’t here a few days ago!’ Ingrid replies. ‘Every time we come, there is something new.’

Some Cool Corfu Souvenirs

Sarandë’s changing faces are juxtaposed as we drive through the city. We pass a palm-lined waterfront promenade with smart restaurants and cafe-bars, a cow grazing on a vacant city lot, and women selling fresh mussels from big baskets on a street corner. Nearly every car we pass is a Mercedes of some shape or size.

‘The Albanians say it’s the only car that can cope with our roads,’ Ben says when we ask why there are so many. ‘You can buy one very cheaply here.’ With a little prodding, we find out that until the police caught on, German motorists were colluding in the scam, reporting their cars ‘stolen’, getting a new car with the insurance claim, and pocketing a few thousand euros for the old one.

We drive up a steep hill to Castle Lekuresi, now a top restaurant, for a coffee and the stupendous view over the bay. On the way down our mini-van, a Fiat Ulysses, starts overheating. ‘This is what happens when you don’t have a Mercedes,’ Ingrid says.

So it’s back to town to hire a taxi for the day and sure enough, it’s a Mercedes. Finally we’re off to Gjirokaster, and we soon take Ben’s point about the roads. The bumpy tarmac winds through a lush countryside of fertile fields and hillsides with flowering yellow sage and pink Judas trees. Enterprising locals have set up roadside stands beneath the trees, chilling watermelons, cherries and soft drinks in the streams. Others run makeshift car washes beside the river.

Over the top of a hill a wide plain opens up below us, backed by a stunning range of rugged, white-capped mountains. Ben tells us the Greek border is only 5km away. Despite their beauty, few outsiders venture into the mountains, where tales of blood feuds and armed bandits are not entirely a thing of the past.

Ben’s father is the famous Albanian poet, Lefter Cipa. One night he was travelling in a car with three other men when they were stopped by the police who were looking for armed bandits. He held up a book of his poetry and told them ‘This is my only weapon’. The policemen laughed and sent them on their way.

As we descend into the valley, a line of concrete pillboxes spreads across a field below. It looks like a row of skull tops. Hoxha’s bunkers are Albania’s most infamous sight. The dictator was so paranoid about invasion that he built some 300,000 of them to control the country. You see them everywhere, large and small, not just along the coast and borders but in unlikely places, even people’s front gardens.

‘It cost the country a lot of money,’ Ben said. ‘One bunker equalled the price of one flat. Now it costs too much to destroy them, they were built to withstand aerial bombs, and no one knows what to do with them.’

The old town of Gjirokaster is a UNESCO World Heritage Site, with traditional houses perched on steep hillsides below a castle. Enver Hoxha was born here in 1908, in a grand old Turkish-style mansion built of stone with wooden balconies. Rebuilt after a fire, it is now an Ethnographic Museum portraying traditional family life, albeit an upper-class one. The communist leader clearly came from a life of privilege.

The 13th-century castle is an amazing fortress, with walls three metres thick and arches built of stone. It was a prison until 1968 and now houses a military museum of sorts, with displays of arms from the Stone Age to World War II, mostly from other countries. There is, however, an exhibit on another of Gjirokaster’s native sons, the writer Ismail Kadare, winner of the first international Man-Booker prize.

That night, over drinks on the promenade back in Sarandë, with lights twinkling prettily round the bay, we think that we could be almost anywhere in the Mediterranean. Indeed, many locals see the town’s future as a seaside resort. This is apparent the next day as we drive along the coast to Butrint. The coast is part of the so-called Albanian Riviera, and there are dozens of villas and hotels under construction. Curiously, many sites had scarecrows on the open rooftops.

‘It’s to ward off evil spirits,’ Ingrid explained. ‘You’ll often see little dolls on Albanian houses for the same reason.’

We pass Lake Butrint, with its large mussel beds. Further along its shore we enter the archaeological site of Butrint. Now part of a national park covering 29 sq km, it rivals any ancient site in Greece. Dating back to at least 1000 BC, the well-preserved ruins contain prehistoric walls, Greek temples, Roman mosaics and a Byzantine church, winding through a verdant, atmospheric setting.

On the way back to Sarandë we wonder who will fill all those new hotels. Foreign tourist numbers are still small. Perhaps what Albania needs is more impressive sites like Butrint to attract them. Although a sense of anarchy from the old days still lingers under the surface, the Albanians seem an enterprising lot.

Someone has even made good use of Hoxha’s bunkers. From the corniche road we see them along the sea, painted in bright colours and designs. Beach huts? Or simply works of art, an artistic statement on the new Albania.

As we leave our hotel the next morning, we spy a little doll, tacked up on a second floor balcony for good luck. Ingrid notices a group of builders erecting a wall in the car park. ‘Typical,’ she observes, ‘One is working and three are watching.’

Some things never change.

All Photos (c) Mike Gerrard

To book a trip from Corfu to Albania, or to rent a car on Corfu, find accommodation, book a yacht or do many other things on Corfu, visit the website of Sipa Tours.

If you want to arrange your own visit, find hotels in Sarande using the search box:

Latest Posts

-

Greek Ferry Services to Halt on May 1 Due to Labor Strike

Ferries in Greece will remain docked for 24 hours on Thursday, May 1, as the Pan-Hellenic Seamen’s Federation (PNO) joins Labor Day mobilizations announced by the General Confederation of Greek Labor… -

Easter in the Mystical Castle of Monemvasia

In the castle town of Monemvasia, with its dramatic medieval backdrop and sea views, Easter is a deeply spiritual and atmospheric experience. -

Easter in Leonidio: A Tapestry of Light, Culture and Cliffs

In Leonidio, Easter comes alive with handmade hot air balloons in the sky and lanterns made from bitter oranges in the streets. -

The Lesser-Known Traditions of Greek Easter

Step off the beaten path this spring and discover the enchanting — and often surprising — Easter traditions found across Greece. -

Sifnos: Greece’s Hidden Culinary Star on the Rise

Sifnos, a Cycladic island, is gaining fame for its rich culinary heritage, especially the beloved melopita honey-cheese tart. -

April 9 Strike in Greece to Impact Public Transport, Ferries and Air Travel

Transportation and travel across Greece will face disruptions on Wednesday, April 9, as public transport, ferry and aviation workers join a nationwide strike called by Greek labor unions. -

Ancient Theater of Lefkada Brought Fully to Light Following Systematic Excavation

The Greek Culture Ministry has announced that the first ancient theater ever identified in the Ionian Islands has recently been brought fully to light on Lefkada, revealing an impressive monument that… -

Seven Greek Traditions Recognized as Intangible Cultural Heritage

From traditional barrel-making to age-old folk dances, seven new entries on Greece’s National Inventory preserve the country’s living heritage for future generations. -

Greek Air Traffic Controllers to Hold 24-hour Strike, Disrupting Flights on April 9

The Hellenic Air Traffic Controllers Union have announced a 24-hour strike for Wednesday, April 9, in response to the protest called by the Civil Servants’ Confederation (ADEDY). The strike is being h… -

Ten Best Budget Hotels on Santorini

Greece Travel Secrets picks the ten best budget hotels on Santorini, some with caldera views, some near beaches and some close to the heart of Fira.