Irakleio’s Archaeological Museum

Irakleio’s Archaeological Museum is Crete’s most important museum and contains some of Crete’s oldest artefacts, Minoan frescoes and the Phaistos Disc.

Irákleio’s Archaeological Museum is not only the major museum on Crete, it is the largest repository of Minoan antiquities anywhere, and stands among the finest museums of the ancient world. This magnificent collection of pottery, frescoes, jewellery, ritual objects and utensils brings the Minoan world to life.

Come here first before visiting the ancient palaces and your view of the ruins will be enlivened with a sense of the colour, creativity and richness of the fascinating culture that once flourished on this island. It is definitely a Must-See site in Irakleio.

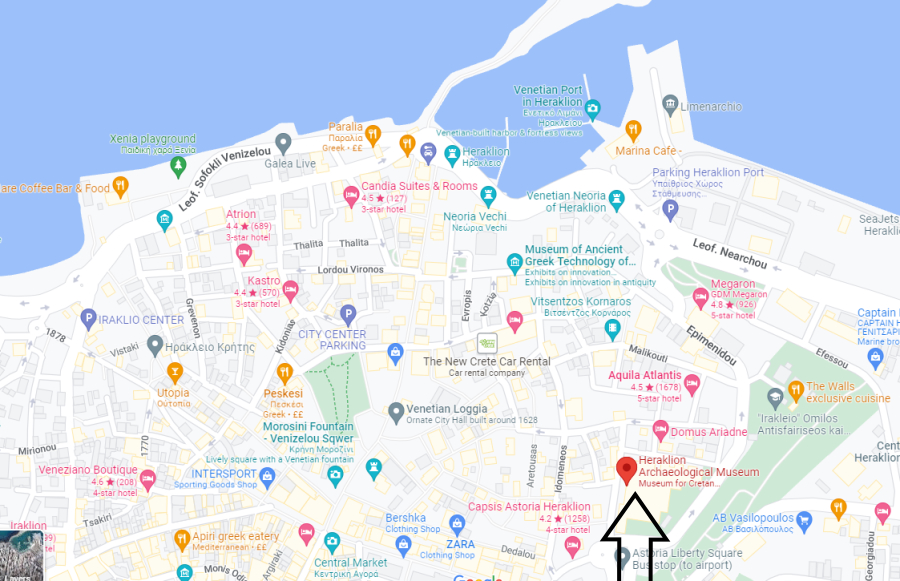

Where Is Irakleio's Archaeological Museum?

Map (c) Google Maps

Map (c) Google MapsIrakleio’s Archaeological Museum

The Archaeological Museum covers 5,500 years of Cretan history, dating from Neolithic times (5000-2600 BC) to the end of the Roman era (4th century AD). The two-storey building, which contains 20 galleries, was built in 1937-40 and underwent a massive renovation project between 2006 and 2013.

Visiting Irakleio’s Archaeological Museum

Inside the entrance hall is a large desk where you can buy postcards and a museum guide. This is not essential, as most of the major exhibits are labelled in both Greek and English, though not in great detail. You can also print out a PDF of our guide to the museum's highlights. See the link at the bottom of the page.

The collection is arranged chronologically from room to room, with finds from the major Minoan periods also grouped according to the sites where they were discovered.

Top Tip

Visit first thing in the morning, during lunchtime or in the late afternoon to avoid the worst of the coach-party crowds.

Timeline

Archaeologists categorise the museum’s artefacts into the following periods:

- Pre-palatial period: 2600—1900 BC

- Old Palace period: 1900—1700 BC

- New Palace period: 1700—1450 BC

- Late Palace period: 1450—1400 BC

- Post-Palace period: 1400—1150 BC

- Sub-Minoan, Geometric, Oriental and Archaic periods: 1150—6th century BC

- Classical, Hellenistic and Roman periods: 5th century BC—4th century AD

Minoan Motifs

Look for the major motifs which appear on artefacts throughout Minoan times: the double ax, the spiral and the horns of consecration were often painted or etched on pottery, while votive figurines were shaped like bulls or goddesses with upraised arms.

Irakleio’s Archaeological Museum Room I

Room I contains some of Crete’s oldest artefacts, ranging from Neolithic stone tools and crude idols, to early Minoan pottery, figurines and jewellery from the Pre-palatial period. The ancient origins of bull sports, later an important ritual in palace life, are depicted by the small clay figures of bulls with acrobats grasping their horns, in case 12-13 and case 15.

Look out too for early signs of Minoan craftsmanship in the Vassilikí pottery from eastern Crete, with graceful, elongated spouts and deep red and black mottling, obtained by uneven firing. Also noteworthy are the early seal stones.

Must See

- The Phaistos Disc (Room III)

- Snake Goddesses (Room IV)

- The Bull’s Head Rhyton (Room IV)

- Rock Crystal Rhyton (Room VIII)

- Hall of the Frescoes (Rooms XIV-XVI)

Irakleio’s Archaeological Museum Room II

Room II contains Old Palace finds from Knossos and Mália. The painted and glazed earthenware plaques of the Town Mosaic (case 25) depict the multi-storey dwellings of Minoan architecture. The many human and animal figurines were votive offerings found in peak sanctuaries.

Clay taximata, representing feet, arms or other parts of the body needing cures, are forerunners of the silver ones pinned to icons in churches today. Pottery is more elaborate with the white and red polychrome decoration of Kamáres ware, and the delicate ‘egg shell’ cups.

Irakleio’s Archaeological Museum Room III

The Phaistos Disc

The Phaistos DiscThe style reaches its height in Room III, devoted to finds from the same period at Phaistos palace. Here large amphorae sport elaborated spirals, fish and other designs, while the royal banquet set (case 43) includes a huge fruit stand and a jug with relief decoration of big white flowers. However, the highlight of this room is the Phaistos Disc with its intricately carved hieroglyphic characters, possibly from a ritual text. It stands alone in a central case.

Irakleio’s Archaeological Museum Room IV

Room IV contains some of the finest artworks in the museum, dating from the New Palace period when Minoan art reached its peak. As you enter, in the left corner is an exquisite gaming board from Knossos, made of ivory with gold casing and inlaid decoration of rock crystal and lapis lazuli.

Further along this wall in case 50 are two superb statues of the Snake Goddess, sacral relics from the temple repositories. Both are bare-breasted, one holding a pair of snakes in her upraised arms, the other with snakes coiled round her outstretched arms. They represent a major Minoan deity, or possibly a priestess engaged in ritual.

Case 51 contains the Bull’s Head Rhyton from Knossos (a rhyton is a libation vessel used in religious ceremonies). Magnificently carved from steatite, a black stone, it has inlaid eyes of rock crystal, nostrils of white shell and restored wooden horns.

Other life-like artworks are equally impressive, such as the alabaster head of a lioness, also a libation vessel, and a stone axe-head carved in the shape of a panther (both from Mália in case 47); and in case 56 the graceful ivory figure of an acrobat in mid-leap. New developments in pottery are represented by the Jug of Reeds, case 49, with dark colours and patterns depicting nature themes.

Top Tip

You don’t need to tackle all the exhibits at once. Your ticket is valid for re-entry on the same day, so take a break if you’re feeling tired or overwhelmed.

Irakleio’s Archaeological Museum Room V

Room V, with Late Palace period finds from the Knossos area, has an interesting model of a Minoan house at Archánes. Case 69 contains rare examples of Linear A script, the written language of the Minoans, alongside the Linear B script of mainland Greece.

Europe’s First Written Word

The earliest known written history in Europe began in Crete around 2000 BC. Known as Linear A, these inscriptions pre-date the documents of Mycenean Greece, written in Linear B, by 600 years. Nearly 1,600 Linear A inscriptions have been found to date, and although they are not fully deciphered, most are probably administrative records. Only 10 per cent, found in sacred caves and mountains, are thought to be religious in nature.

Irakleio’s Archaeological Museum Room VI

Room VI contains a range of objects from cemeteries at Knossos and Phaistos. In case 71 is a delightful clay statuette of men locking arms in a ritual dance between the horns of consecration, and another clay scene of ritual washing. Along the back wall are the bizarre remains of a horse burial, while case 78 contains a helmet made of boars’ tusks. There are also several cases of jewellery and bronze objects.

Parting Gifts

Men were buried with bronze weapons and tools, while bronze mirrors were beloved offerings for female burials.

Irakleio’s Archaeological Museum Room VII

Three enormous bronze double axes erected on wooden poles guard the entrance to Room VII. Religious objects often decorated the hallways of palaces and country villas. The most outstanding piece of Minoan jewellery ever found — the intricate honeybee pendant with two gold bees joined round a honeycomb — is tucked away among the displays of jewellery in case 101 at the back of the room.

Equally famous are three elegantly carved steatite vases from Ayía Triádha (cases 94—96): the Harvester Vase shows a procession of harvesters and musicians; the Chieftain Cup portrays an official receiving a tribute of animal skins; the Boxer Rhyton depicts boxing, wrestling and bull-leaping.

Irakleio’s Archaeological Museum Room VIII

Room VIII is devoted to treasures from the palace of Zákros. In case 109 along the wall is one of the triumphs of the museum — a stunning rock crystal rhyton with a green beaded handle, expertly reconstructed from over 300 fragments. The Peak Sanctuary rhyton in case 111 depicts scenes of Minoan worship. Room IX contains finds from settlements in eastern Crete, including Gourniá, and has a marvellous collection of seal stones.

Small is Beautiful

Despite their tiny size, seal stones display an amazing degree of craftsmanship. Animals, people, imaginary creatures and hunting or religious scenes were carved in intricate detail onto hard stones such as agate or amethyst. These were then impressed onto clay seals which were used as a signature on correspondence or a guarantee on shipments of goods. No two are alike.

Irakleio’s Archaeological Museum Room X and XII

Rooms X-XII represent the Post-Palatial periods. Here, Minoan art is in decline, and the influences of Mycenaean Greece and Egypt are apparent. Room XIII contains dozens of clay sarcophagi (coffins) painted with geometric designs. Many are shaped like bathtubs, and two have skeletons intact.

Irakleio’s Archaeological Museum Room XIV

Upstairs, Room XIV, the Hall of Frescoes, is the highlight of the museum. The long walls are lined with the famous frescoes from Knossos: the bull-leaper, the Lily Prince, the dolphins from the Queen’s bedroom. Only fragments of the original frescoes survive, with the paintings reconstructed around them, but the colour and detail in these few pieces reveal the remarkable skill of these ancient artists.

In the centre of the room is the magnificent Ayía Triádha sarcophagus, which survives intact, with elaborate scenes of a funeral procession and animal sacrifice.

Irakleio’s Archaeological Museum Rooms XV and XVI

Rooms XV and XVI have smaller frescoes, including the sensuous ‘La Parisienne’ (no. 27). Also notice the ‘Saffron Gatherer’, originally thought to be a boy picking flowers but later re-interpreted as a blue monkey.

Hidden Gems

Don’t overlook the hidden gems, such as the seal stones, the honeybee pendant (room VII) or the ivory butterfly (room VIII). The museum’s garden has the ruins of the Venetian Monastery of St Francis, too.

Irakleio’s Archaeological Museum Rooms XIX and XX

At the end of the Hall of Frescoes is a wooden scale model of the Palace of Knossos in all its glory. Back on the ground floor, rooms XIX and XX contain classical Greek and Roman sculpture.

More Information on Irakleio’s Archaeological Museum

Visit the Irakleio Archaeological Museum website.

Print a PDF

If you want to print the relevant text from our guide out as a PDF to take with you while you tour Irakleio’s Archaeological Museum, click here.

Latest Posts

-

The Lesser-Known Traditions of Greek Easter

Step off the beaten path this spring and discover the enchanting — and often surprising — Easter traditions found across Greece. -

Easter in the Mystical Castle of Monemvasia

In the castle town of Monemvasia, with its dramatic medieval backdrop and sea views, Easter is a deeply spiritual and atmospheric experience. -

Sifnos: Greece’s Hidden Culinary Star on the Rise

Sifnos, a Cycladic island, is gaining fame for its rich culinary heritage, especially the beloved melopita honey-cheese tart. -

Easter in Leonidio: A Tapestry of Light, Culture and Cliffs

In Leonidio, Easter comes alive with handmade hot air balloons in the sky and lanterns made from bitter oranges in the streets. -

April 9 Strike in Greece to Impact Public Transport, Ferries and Air Travel

Transportation and travel across Greece will face disruptions on Wednesday, April 9, as public transport, ferry and aviation workers join a nationwide strike called by Greek labor unions. -

Ancient Theater of Lefkada Brought Fully to Light Following Systematic Excavation

The Greek Culture Ministry has announced that the first ancient theater ever identified in the Ionian Islands has recently been brought fully to light on Lefkada, revealing an impressive monument that… -

Seven Greek Traditions Recognized as Intangible Cultural Heritage

From traditional barrel-making to age-old folk dances, seven new entries on Greece’s National Inventory preserve the country’s living heritage for future generations. -

Greek Air Traffic Controllers to Hold 24-hour Strike, Disrupting Flights on April 9

The Hellenic Air Traffic Controllers Union have announced a 24-hour strike for Wednesday, April 9, in response to the protest called by the Civil Servants’ Confederation (ADEDY). The strike is being h… -

Ten Best Budget Hotels on Santorini

Greece Travel Secrets picks the ten best budget hotels on Santorini, some with caldera views, some near beaches and some close to the heart of Fira. -

No Ferries in Greece on April 9 as Seamen Join Nationwide Strike

The Pan-Hellenic Seamen’s Federation (PNO) has announced its participation in the 24-hour strike called by the General Confederation of Greek Labor (GSEE) on Wednesday, April 9. The strike, which will…